Mitch’s Blog

Why Publishers Should Not Write Memoirs

Wednesday, June 14, 2023

I haven’t read the book, nor have I seen the movie. There won’t be one. I don’t even know the guy. I’ll be the first to admit to being wildly unfair. But, for the few people who’ve wondered why I don’t write my memoirs, I have a solid answer.

Publishers are boring.

Not as people, many of them are fascinating characters with wide interests. One publisher friend became a novelist. Another doubles as a salsa teacher. They’re always well read, interested in and able to intelligently discuss almost any topic. Most of them write well: they’ve seen more badly written manuscripts than any human should be forced to read who has not been condemned to Dante's 7th circle. But publishers writing memoirs about publishing is a book category that should be abolished.

I’ll be picking on Richard Charkin here, though he probably doesn’t deserve it. He’s held senior posts in such august organizations as Macmillan, Oxford, Pergamon, Bloomsbury, Reed Elsevier. and Institute of Physics Publishing and has held a host of other key industry roles.

I’ve picked on Charkin before, when he announced in the Publishing Perspectives newsletter that he was founding his own small publishing house after stepping down from the director’s floor of Bloomsbury. His trials were revealed in a series of blogs in the following year. They were highly amusing to someone who spent 20 years in the trenches after starting small presses—twice—without having had the luxury of a previous position with a private secretary, unlimited travel account, access to lines of credit, and to the ears of journalists and members of Parliament. I couldn’t even get Amazon to answer my emails, and they sold most of our books.

Charkin’s memoir, My Back Pages, coauthored with professional writer Tom Campbell, has just published by Marble Hill Publishers. Charkin knows the publishing aspect of an author’s work. He had Publishing Perspectives publish five excerpts of the book as teasers before the publication date, which coincided with the London Book Fair, where he had a book signing. Great way to advertise your new book, isn’t it? I read his excepts with interest. What would a publisher of his distinction have to say?

Charkin’s memoir, My Back Pages, coauthored with professional writer Tom Campbell, has just published by Marble Hill Publishers. Charkin knows the publishing aspect of an author’s work. He had Publishing Perspectives publish five excerpts of the book as teasers before the publication date, which coincided with the London Book Fair, where he had a book signing. Great way to advertise your new book, isn’t it? I read his excepts with interest. What would a publisher of his distinction have to say?

His most recent column was a reflection on turning from publisher to author. I’ve done the same, leaving the helm of Left Coast Press and becoming author and/or editor of three volumes on Afghanistan in the past 3 years. Charkin struggled to produce his 65,000 word manuscript. My most recent one runs four times that length, and that’s without a ghost writer.

He sums up his experience

Writing is hard. Editing is essential. Publishers add enormously but it is more important to find the right publisher than to chase the money. Try to write to one audience not several, as if talking to a single person. Take criticism in the spirit it’s made. Work hard at every aspect up to and beyond publication date. Enjoy the ride.

No offense, Richard, but this is as pedestrian a description of being an author as one can imagine. This contrasts with some of fairly profound writers who have written about their experiences writing like Stephen King, whom I’ve already blogged about, or Ann Lamott, and numerous scholarly writers on writing like Harry Wolcott, Laurel Richardson, Brian Fagan, and Howard Becker, some of whose books I’ve published.

As a publisher-not-a-writer, I doubt I could do any better job of describing writing as well as these lifetime writers. Not even sure I have something more profound to say about either writing or publishing than Charkin.

This is why publishers don’t write memoirs.

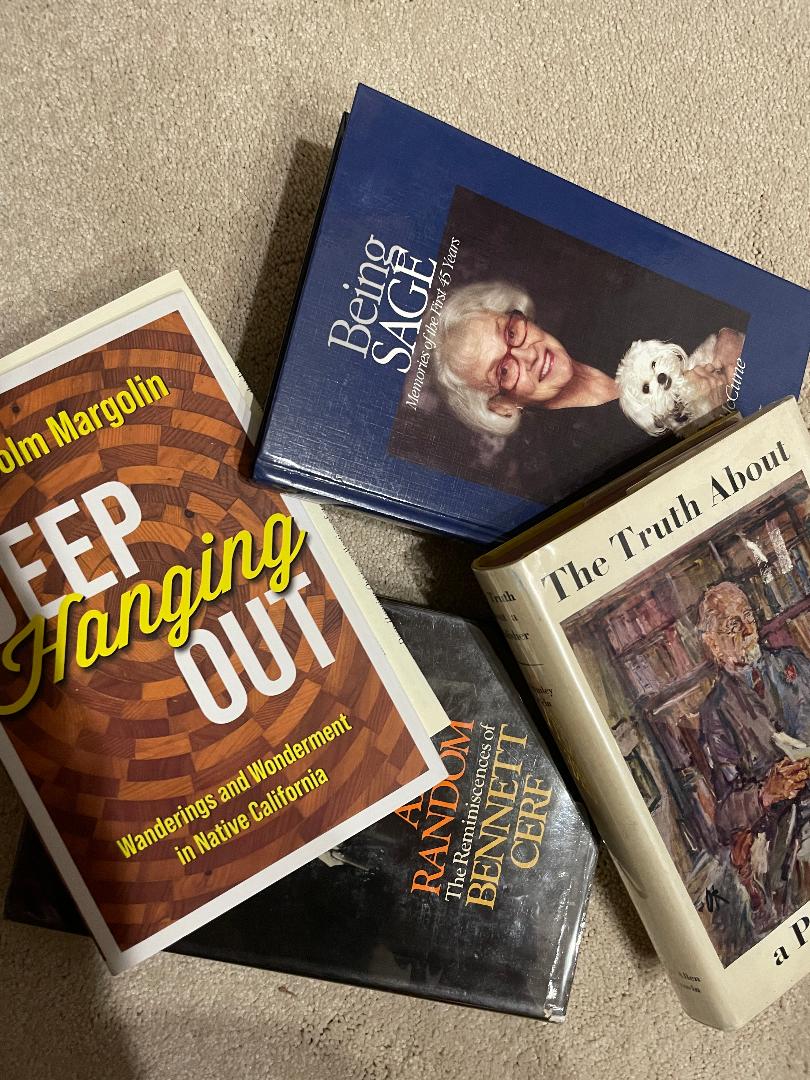

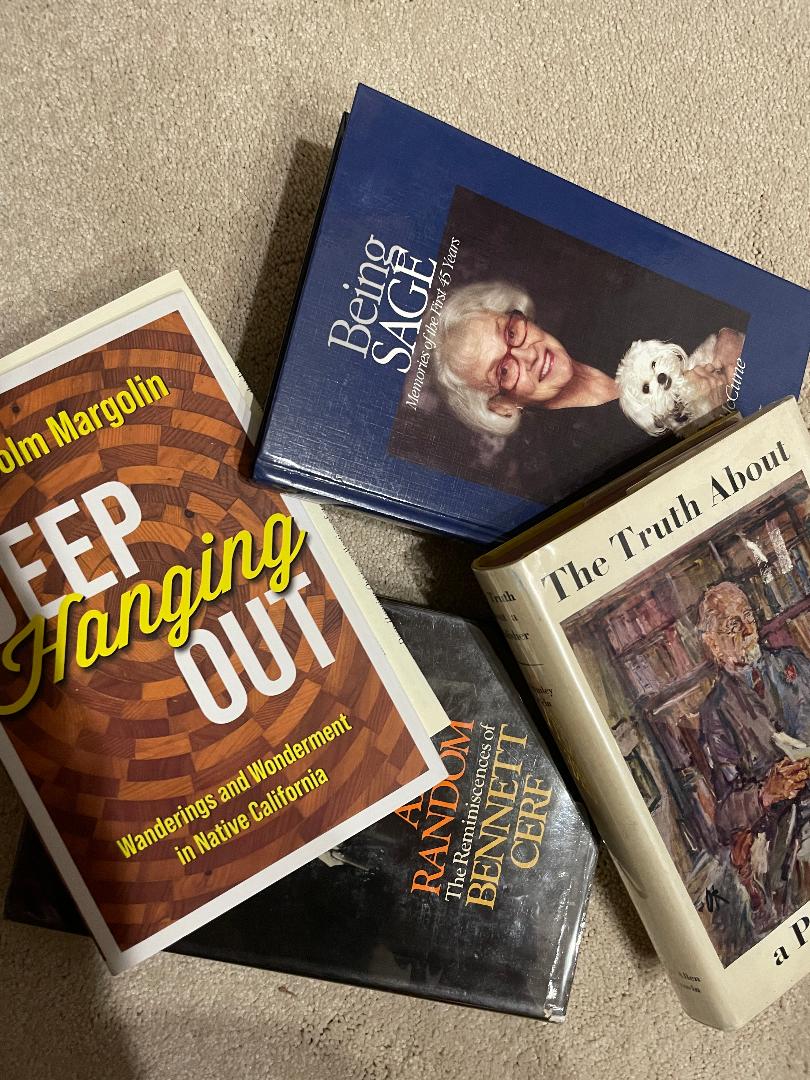

I’ve read a few that crossed my way. Malcolm Margolin, who founded Heyday Books and lived through the Berkeley 60s and after. Famous intellectual Bennett Cerf. Stanley Unwin, who got a Sir before his name in his lifetime. Sara Miller McCune, my mentor and founder of Sage Publications. These are legends in my field. And their stories are downright boring.

I’ve read a few that crossed my way. Malcolm Margolin, who founded Heyday Books and lived through the Berkeley 60s and after. Famous intellectual Bennett Cerf. Stanley Unwin, who got a Sir before his name in his lifetime. Sara Miller McCune, my mentor and founder of Sage Publications. These are legends in my field. And their stories are downright boring.

They rubbed shoulders with genius writers, helped push the writer’s (and their own) careers along, sometimes received recognition for having discovered the next great novelist or essayist. Otherwise, how interesting are the train trips with a bloviated manuscript being red penciled as the author passed Princeton, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh? Even if the manuscript was by Sinclair Lewis.

As for Charkin’s excerpts, there are some interesting facts about London publishing over the decades. If I knew any of the British publishers involved, there might be some juicy gossip, but I operated out of California. The most interesting story was that Pergamon had a Miss Pergamon prize for women in the 1970s, which included a trip to Paris and a wardrobe for the winner. Applicants had to supply a bathing suit photo and their vital statistics, which I assume didn’t include their SAT results.

Does any true drama well up in a publisher’s world? The wrong cover being printed on the 100 copies of a book shipped to a book signing event? The discovery of joint interest in bass fishing being the basis of a lifelong author-editor relationship? Battles with the accounting department over reimbursement of a dinner at Chez Panisse? The terror of a bad pastrami sandwich at New York’s Stage Deli?

I met Harry Wolcott in adjoining urinals in some Hilton bathroom at some anthropology conference. I started up a conversation that turned into a decades-long publishing partnership. TMI.

Scott Berg’s biography of editor Maxwell Perkins, not even a memoir, managed to bust out of the genre by being made into a motion picture, Genius, depicting his dealings with people named Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Rawlings, and Wolfe. The book was less than a page turner. So was the movie, despite the colorful batch of authors Perkins had to deal with. What we publishers do is just not all that dramatic or interesting.

Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Rawlings, and Wolfe. The book was less than a page turner. So was the movie, despite the colorful batch of authors Perkins had to deal with. What we publishers do is just not all that dramatic or interesting.

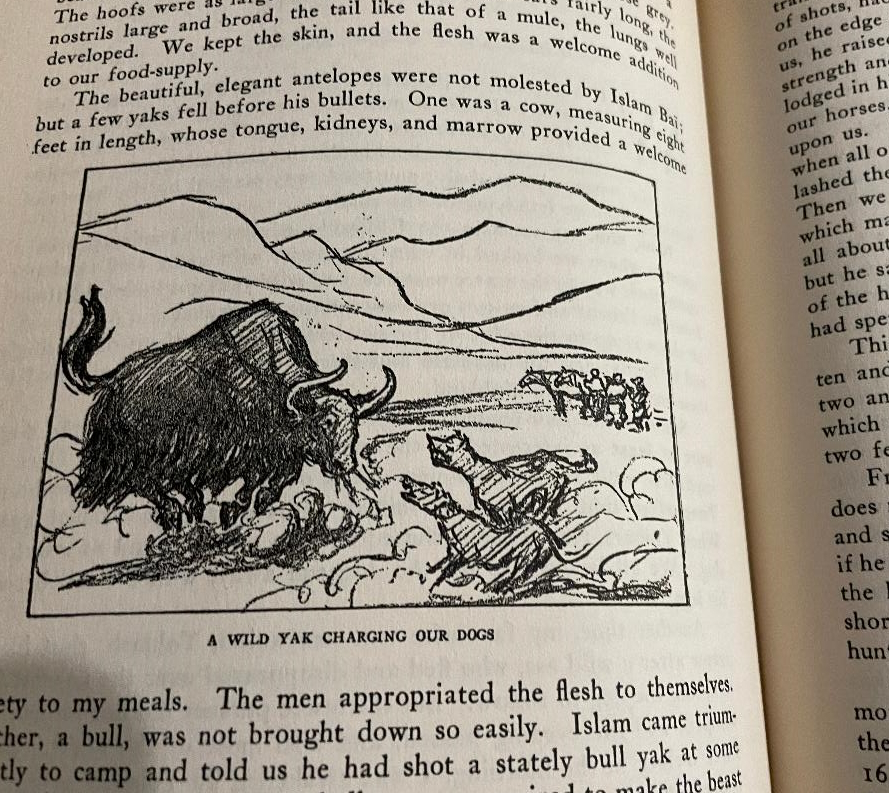

I’ve recently had to read a different set of memoirs. There is little written history about the early rediscovery of the ancient remains that dot Afghanistan appearing anywhere but in the memoirs of the 19th century European explorers, soldiers, highwaymen, and grifters who flowed through the area. Take Sven Hedin, a Swedish explorer, who spent 4 decades early in the 20t h century trekking through Tibet, Turkestan, Afghanistan, and China filling in blank spots on European maps, identifying countless archaeological sites and cultural groups previously unknown in the west, and confronting bandits, dictatorial village chiefs, and wild yaks in his journeys. He wrote about all this in his memoir.

h century trekking through Tibet, Turkestan, Afghanistan, and China filling in blank spots on European maps, identifying countless archaeological sites and cultural groups previously unknown in the west, and confronting bandits, dictatorial village chiefs, and wild yaks in his journeys. He wrote about all this in his memoir.

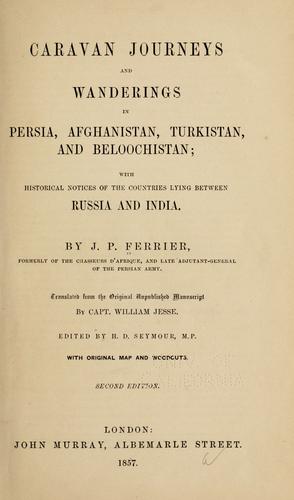

Or, even earlier, J.P. Ferrier, who wandered around western Afghanistan and spent much of his time in prison, being unable to convince his guards that he was not a British spy, but a French traveler. Afghanistan had just concluded a bitter war against England (1839-1842) and, after all, don’t all Europeans look alike? I read Ferrier carefully as he describes the abandoned building he hid in while being chased by a band of Baluch raiders. We identified and studied that building 150 years later. Now those are memoirs.

So, dear readers. I know you’re aching with disappointment, but I’m afraid the Memoirs of Mitchell Allen, Publisher, will never be stacked on your To Be Read bookshelf with the 20 other books you’ll never get to. Enough if you’ve made it to the end of today’s screed. You don’t need to hear any more from a publisher.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life