Mitch’s Blog

What Happened to that Grecian Urn?

Saturday, March 16, 2019

I’ve talked often about my archaeological “legacy” project from Afghanistan, where the field work was conducted back in the 1970s, and I’m only now pulling together the material for publication. In the process, legacy has taken on new meanings. It’s not just the legacy of the archaeology work nor the contribution to the historical legacy of war-torn Afghanistan. Important legacies have crept into this work, weaving a deep web that crosses continents and many lineages. I’ll speak of one here.

The descendants of John Philip Miller (a pseudonym) has a stake in our work. Miller was an American consultant in Afghanistan and a collector of ancient and ethnographic art, buying antiquities from local villagers to fuel his passion. Greek sculptures and column fragments started coming to him from a single nearby site while he was working in southwest Afghanistan. This was a rarity.  Objects with Greek influence are only known from only the couple of centuries after Alexander the Great marched through on his way to India.

Objects with Greek influence are only known from only the couple of centuries after Alexander the Great marched through on his way to India.

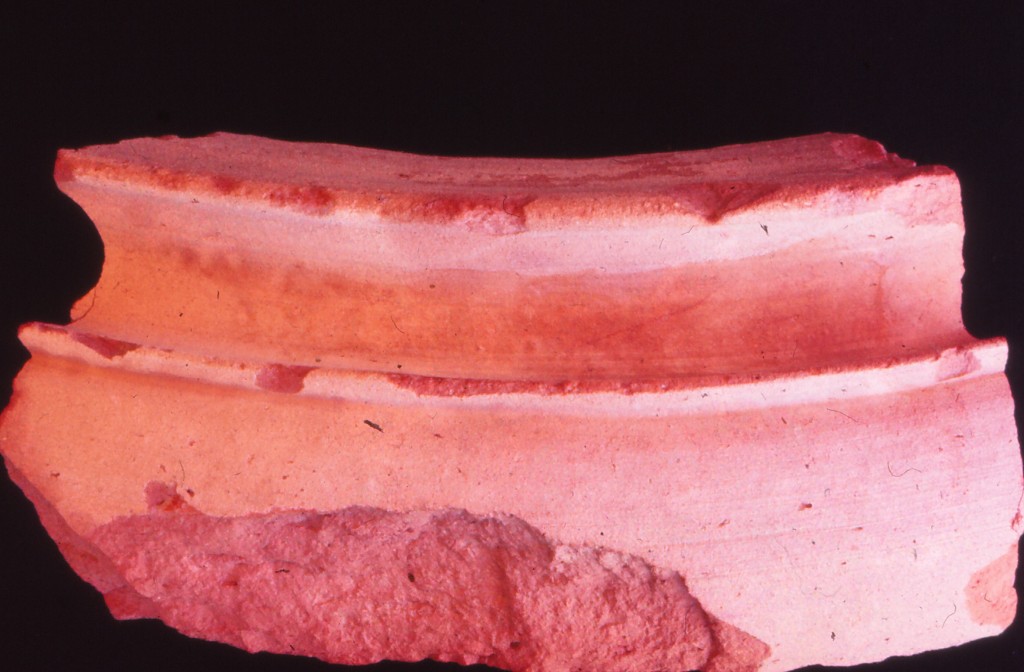

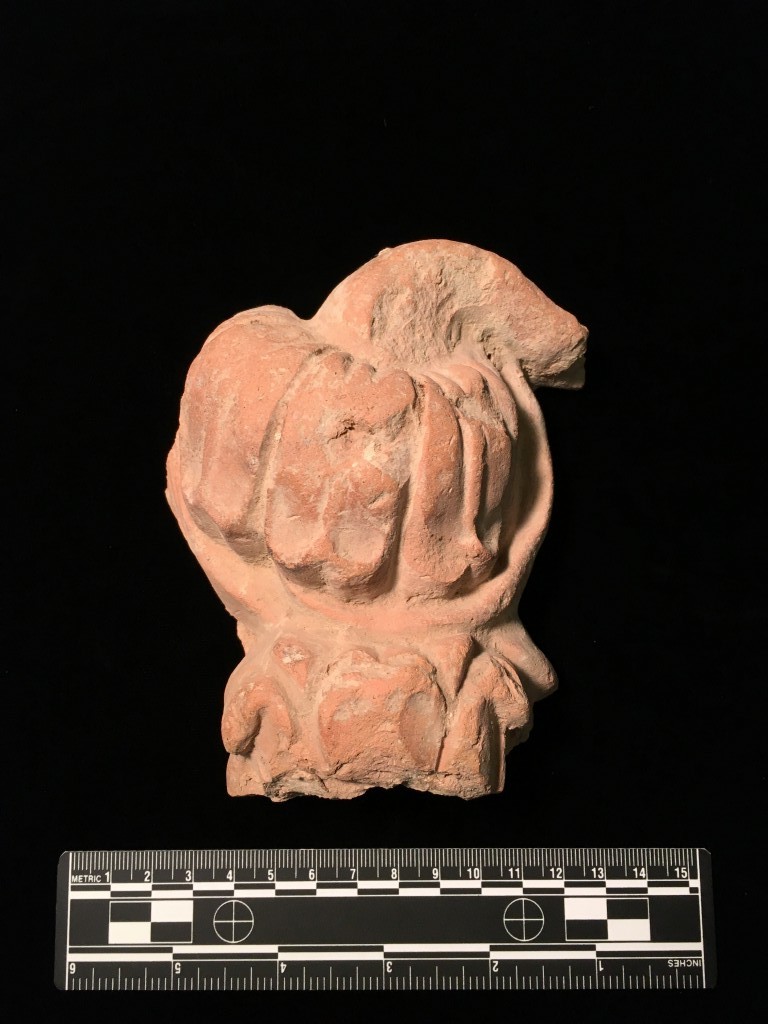

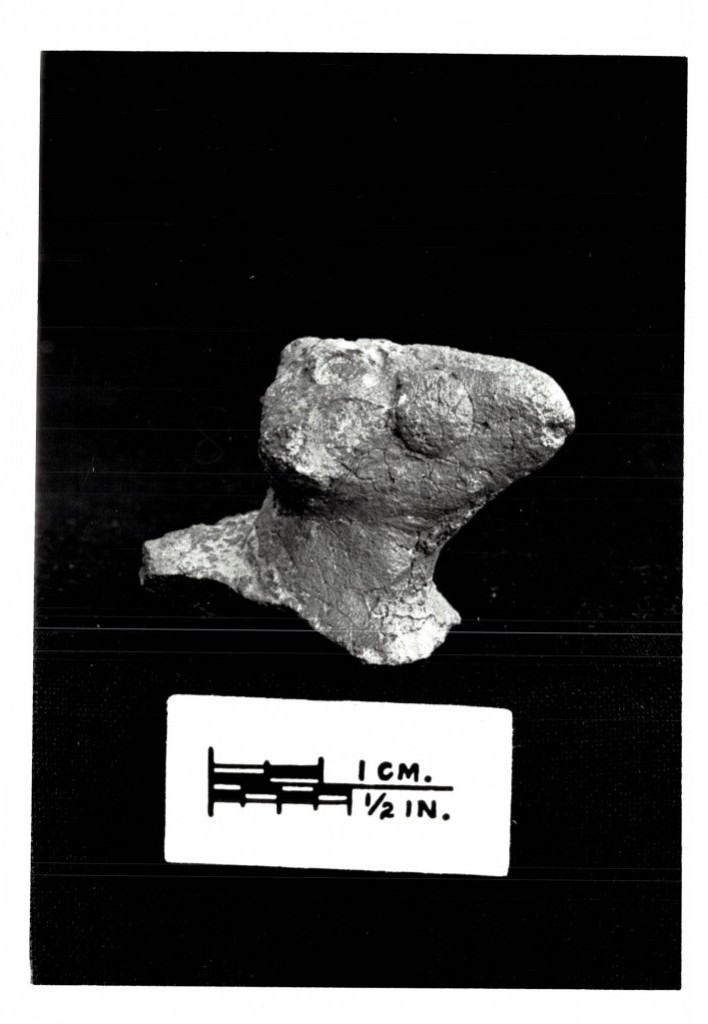

Miller saw an opportunity and concentrated on this lucrative hoard, paying a few locals handsomely to loot the site and bring him every piece they could. There were fractured stone faces with Hellenic curls, slices of carved drapery, rounded column bases of baked brick, garlands, and spirals that would have fit an Athenian palace. Most of all, there were thousands of small ceramic figurines—horses, rams, even an elephant or two. By the time our project arrived on the scene in 1971, he had over 4,000 bits of Greco-Bactrian art from this hillside, a collection that he shared with us and asked us to publish for him. Like the rest of our project, that has yet to happen.

Miller soon left Afghanistan with his treasures for his next assignment in Africa, where he did the same with African masks and carvings, many of which now grace American museums. But nary a word has been heard about the collection from the Greek site. While we had notes and photos from visiting him, it would be better to see the objects themselves and, if the family still had them, convince them to return the hoard to Afghanistan where it belongs.

Why does this matter to me trying to finish my write up of the Sistan region of Afghanistan? The site in question is one of only two Greek-style temples we found in 10 years of work and almost doubles the number found anywhere in the country in the past century. It is a period almost unknown to scholars who study this region, the far reaches of Greek cultural influence after Alexander left his troops to build a few Alexandrias and marry with the locals.

With the help of the Internet, I found that Miller had passed away seven years ago. Found the obituaries extolling his great generosity in giving away this amazing collection of African ethnographic art to deserving museums. Hah!

I located his nephew Jack, whose father inherited Miller’s collections. I write asking for news.

Does the family have the collection? No.

Files related to it? I’ll check his papers but I haven’t seen anything.

What happened to it? My father said he must have given it away to friends over the years.

Four thousand pieces? Maybe he donated them to a museum.

His African collections are in museum but they have his name on them. No reference to a collection of Afghan antiquities with them. Sorry, I can’t help you.

I was not sure he was being frank with me. After all, if you own a collection of looted Greek art, the last thing you want is an archaeologists snooping around. With the trend now pointing toward repatriating stolen works to their host country even at snooty places like the Met and the British Museum, admitting that he has them could only cause him trouble.

I tried to decide which discussion fills the Miller household.

“Should we tell him where the things are?”

or

“I wonder what Uncle John did with all that stuff.”

Stalemate. The issue just sat until a month ago when a senior French archaeologist, who had seen pictures of these objects in a presentation 40 years ago (another legacy), asked to use them in an article he was writing. Many academic societies are leery of publishing objects thought to be looted and many of their journals forbid it. But if those ceramic elephants and baked brick garlands are now sitting on the shelves in Friends of John households around the world or popping up on eBay, maybe this is the only way this collection can be used to contribute to Afghanistan’s heritage. I share the photos and notes with the scholar.

After publishing for museums for two decades, I was sure of one thing. Someone at the museum, especially a university museum, had worked there long enough to remember the acquisition of the collection, even if it was 30 years ago. It’s not just objects that museum collect.

I was not wrong.

Janet, from Museum 2, responds that her institution doesn’t have anything from Afghanistan. She had been the point person when the African collection first came to her museum, spent a lot of time talking with Miller. From her tone, she liked him a lot and was hesitant with me because I had implied that he was a looter. He was a man of many stories, she said. If he was constantly regaling people about his exploits overseas, he must have mentioned the objects from Afghanistan. Sure enough, he did. But Janet reaffirmed the family claim that he no longer had them. She had visited his remote retirement house and seen no hint of them. Went to his funeral and walked through his estate material afterwards with the surviving family. No Grecian urns.

Leroy, from Museum 1, had also talked directly with Miller. His story was slightly different. Miller had been caught with all this stuff and the Afghan government made him hand most of it over before unceremoniously escorting him out of the country. He was allowed to leave with only a small handful of the objects he had collected. And they were in the basement of Museum 1, though not listed in their online collection.

Eureka! A trip to Museum 1 is now obligatory, and Leroy and I will share notes in the interim.

There was one other implication of Leroy’s story. If the bulk of the collection had stayed in Afghanistan, it would have been housed in the National Museum, destroyed and lo oted in the 1990s. The rest of the collection is likely gone. All that is left is our notes.

oted in the 1990s. The rest of the collection is likely gone. All that is left is our notes.

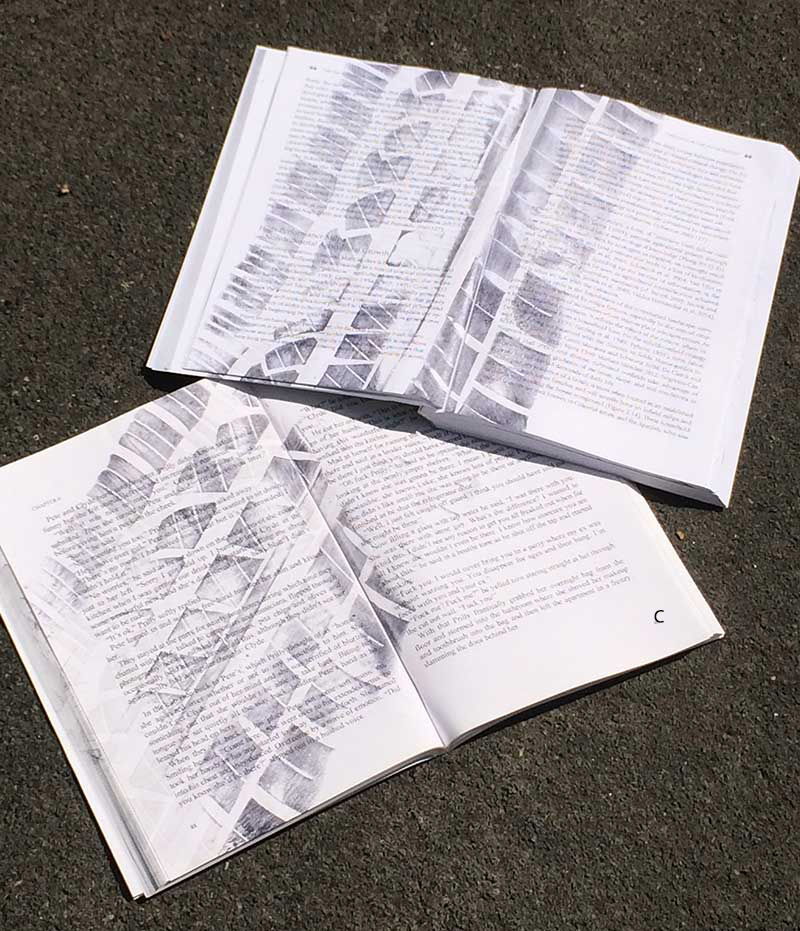

Back in 1971, and based upon Miller’s description, we had visited the hill where the temple supposedly stood. We too found bits and pieces of Greek art and architecture, but our few hours on the site produced just a fraction of the wealth that Miller’s looters had brought to him. We did discover that there was no temple there. Instead, it was the grave of a recent Islamic holy man for whom people had deposited these as offering taken from somewhere else, a common practice in this part of the world. No wonder it was so easy to find so many pieces on the surface.

As for the location of the real Greek temple, stripped by people bringing gifts to their departed imam? We think we know where that is too, but going back to excavate it will not be possible for years, maybe decades. Our notes will have to suffice for this generation at least, the only legacy of Alexander, of the John Philip Miller, of the imam, of the Helmand Sistan Project.

© Scholarly Roadside Service

Photos posted here are from the Helmand Sistan Project survey of the looted site, not from Miller’s collection. Photos by Robert K Vincent Jr, Carol Ellick.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life