Mitch’s Blog

Snow Fall

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

Everything was beautiful, until it wasn’t. The back trail to Lake Enos snakes downhill through the firs and around the lake. It’s a bit steep in a few places, but never difficult. The lake is framed by rows of trees, with thick logs floating in the center. Raptors float overhead. Vines, now covered with filigrees of snow on each leaf, dot each side of the trail. A couple of low spots had filled with water, now slick ice, but I carefully dodged those. The snow was almost gone after a week of freezing but dry weather. Made it down three descents with Sasha on her Monday afternoon walk.

These walks are a routine for me and the dog. When we come to Canada, she gets to go to the beach on our morning walk and through one of a dozen different forest trails in the afternoon. The happiest dog alive—much more interesting sniffs than through suburban Walnut Creek. Lake Enos is one of the regular routes, though never before in snow.

These walks are a routine for me and the dog. When we come to Canada, she gets to go to the beach on our morning walk and through one of a dozen different forest trails in the afternoon. The happiest dog alive—much more interesting sniffs than through suburban Walnut Creek. Lake Enos is one of the regular routes, though never before in snow.

No obvious ice at the bottom of the third drop so I increased my pace bit. Temperature a little above freezing so things looked and felt a bit soft. Except for that one spot. That one spot. And suddenly I was on the ground with a searing pain after hearing a crack in my leg. Was it the knee, my traditional vulnerable spot. No, this time it was the ankle. I’m in the forest with my dog, and I’m down.

One narrow tree trunk within crawling distance beckoned. After a test or two, I pulled myself up on it to standing. Walking, though, was clearly not possible back up that steep slippery slope. The dog, first concerned when I yelled, then whining anxious to continue our walk, finally figured out that something was wrong and sat next to me.

I called our neighbors Jim and Karen for help. A well marked trail and they were there quickly. With no crutches in their house, they dragged a broom and a shovel to choose as a cane to help me out. We made it up the first climb leaning on them instead of a broomstick, but I was going no further. There were still two climbs, some icy patches, and half a kilometer to walk out. The ankle felt weird and somewhat painful but not excruciating. I could put no weight on it.

Time to call in the professionals.

John and Shawn, local emergency volunteers were first on the scene. Then came the fire department and finally the EMTs. Determining that there was nothing to be done other than get me to a hospital, they dragged the “Wheel” down the hill, essentially a gurney atop a large wheel. It took all 8 of them to strap me in and push me up to the road where the ambulance awaited. Sasha went home with my neighbors.

John and Shawn, local emergency volunteers were first on the scene. Then came the fire department and finally the EMTs. Determining that there was nothing to be done other than get me to a hospital, they dragged the “Wheel” down the hill, essentially a gurney atop a large wheel. It took all 8 of them to strap me in and push me up to the road where the ambulance awaited. Sasha went home with my neighbors.

It was only then, in the ambulance to Nanaimo Hospital, that Mike took off my shoe and sock and saw the mess. The foot was at a sharp angle to the tibia, a bad dislocation. He was reassuring, and I knew that someone in his job for 22 years had to have seen far worse. All my other vitals were fine and, surprisingly, the pain was modest. Maybe the cold, a degree or two above freezing kept the achng under control?

The next several hours were as expected. Mike warned me, it would be a long stay. Transferred to a wheeled hospital bed, not as interesting as the Wheel but much more comfortable. It was a crowded hospital with all rooms taken. Many were coughing in the waiting room, Covid round 15. I was parked in a hallway and, fortunately fully alert, was able to grab a passing nurse for water or a pisspot when needed. A roll into the xray room, where th

I was wheeled into the room where they were going to “reduce” my ankle back into its proper socket. Yeah, that’s the medical term. Mallory introduced me to her 2nd year resident Andrea, who it seems was going to do the procedure and was getting constant coaching from her senior partner. They also asked if I would mind is several of the nursing students watched the procedure. I would be knocked out so I didn’t care. It was a small, crowded room when the whole team was finally assembled.

Then came the trip. The anaesthetic was attached to a little drip tube on the wrist and I slowly began to feel the sleeping effects. But I never went out, my consciousness stayed with me the whole time, though the room and the medical crowd disappeared. Instead, I was flying through a bright orange sky. Then through a forest. I think I revisited the Galapagos, where we had been last month. There were conversations that I couldn’t follow going on around me. Loudly. Occasionally I would feel a faint push on my injured leg, later recognizing that they were wrapping me up. Truly an out of body experience, I wondered if this what it felt like to be dying. Would I ever wake up or was this the end, soaring toward the brightest of lights.

I had experimented in my college days. My first try as a freshman had an audience of dorm mates, watching a newbie lick an orange tab with Hendrix blasting over headphones. That night was one of the most memorable of my life, with pirate ships floating in the Santa Barbara channel, purple daisies bleeding from their roots when I picked one, and the fire on the beach spinning an endless series of yellow-orange shapes, soft pops, and sharp crackles. A later college experience was a bit more frightening, as I tried to go dancing after dropping in my room. The floor moved to the music, voices came and went from my periphery, and the whirl of activity became intimidating, frightening. Carol walked me back to my apartment, where I spent the rest of the night watching colors, figures, and patterns dance on the ceiling of my room.

This was the closest I’ve ever felt to that night in the past 50 years.

“How long have I been out?”

”About half an hour,” was the nurse’s response. It had felt like days.

The surgery for the breaks would have to be the following day and I chose to go home instead of staying in the overcrowded hospital over night. A pair of crutches, wonderful neighbors a few steps away, a guard dog, and I was sure I could manage for a night. But the hospital was out of crutches. What? WHAT?

They ended up finding a pair.

Jim and Karen brought me home and got me settled. I didn’t need the heavy narcotics that the hospital provided. Sasha curled up next to me.

The next day we were off to the hospital to put plates on those broken ankle bones. Simple huh? Not so. I was an “add” to the day surgery list for the following day so the last surgery for the day. I went through all the paperwork

“no I don’t have a British Columbia or any other Canadian health card. We’ve called our US insurance and they will cover costs.”

“yes, I’m allergic to prednisone. Makes me a crazy man.”

“Here are the medications I take…”

With the waiting room empty except for a loyal boyfriend whose girl had disappeared through the surgery portal an hour earlier, the nurse comes out to tell me that they had an emergency operation needed on a child. Can’t do your today. Come back tomorrow. Who can complain about them handling a child in emergency?

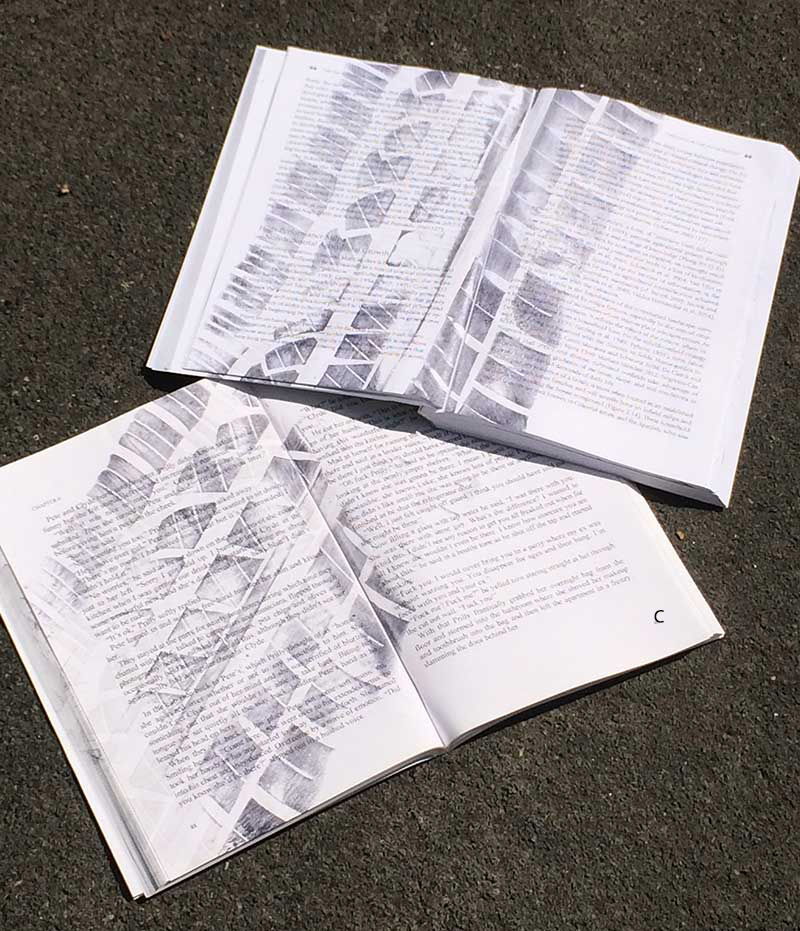

The call on day 3 comes at 8 am. “Please be here by 10 for your surgery.” But the day wasn’t the same cold-but-dry one that preceded it. A rare Parksville snowfall overnight. And even more rare, a heavy one, maybe a foot of white stuff on the ground in a place that gets snow only rarely. Normally, I would be delighted to see the white flakes drifting down out the window while sipping coffee at the table in our warm home. Going out this morning? The side road where we live hadn’t been plowed and there was no idea when it would be. And they had no later appointments that day when the snow plows and the afternoon sun would do their work. Cancelled until day 4.

In the interim, I’ve gotten more comfortable with my crutches, figuring how much I can stuff in my pockets moving from one place to another while I pass another day waiting for the operation. Full coffee cups are a problem. Karen makes me a pot of chicken soup. Julie, another neighbor and an MD, volunteers to rewrap my unraveling bandage, designed to last only a single day and probably wrapped by the inexperienced resident. Jim sweeps snow from the walkway to the car and a path to the trees out back so Sasha can go do her business. The bad weather keeps Vida, who is flying up to care for me, from leaving San Francisco. It pays to have wonderful neighbors.

I’m sure there will be more to this story, but a day with only modest pain, no possibility of going outside, and a lot of free time with a computer became the opportunity to craft this story, incomplete as it is.

© Scholarly Roadside Service. Trail photos by Karen Fedak.

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life