Mitch’s Blog

Culling the Copies

Saturday, May 02, 2020

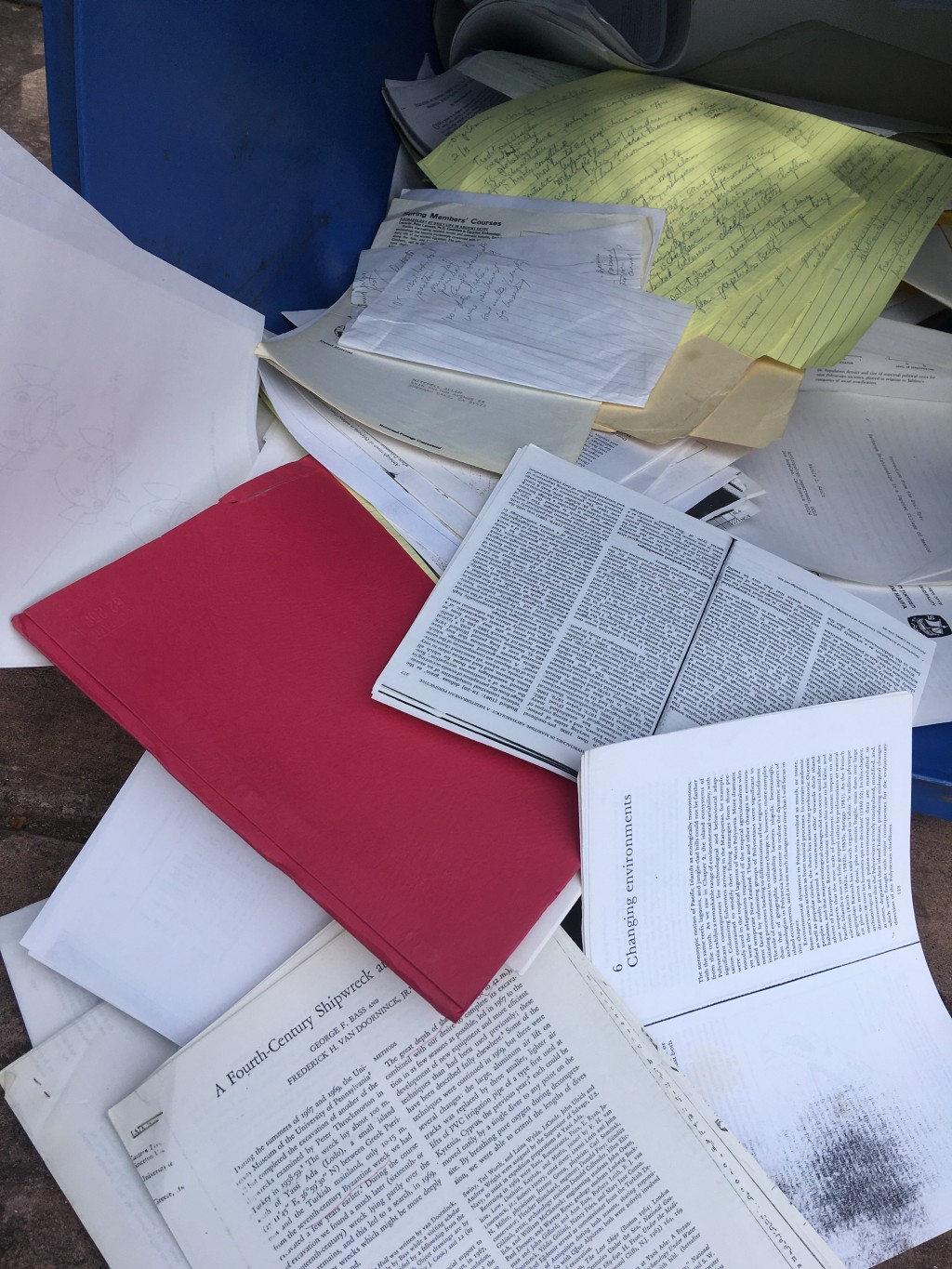

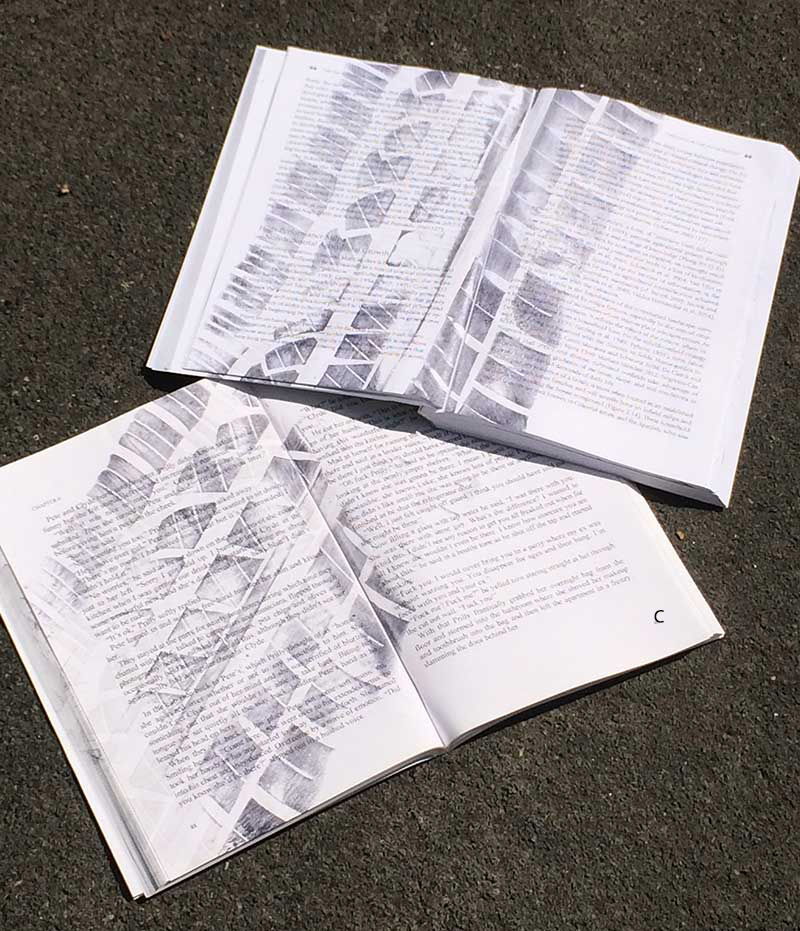

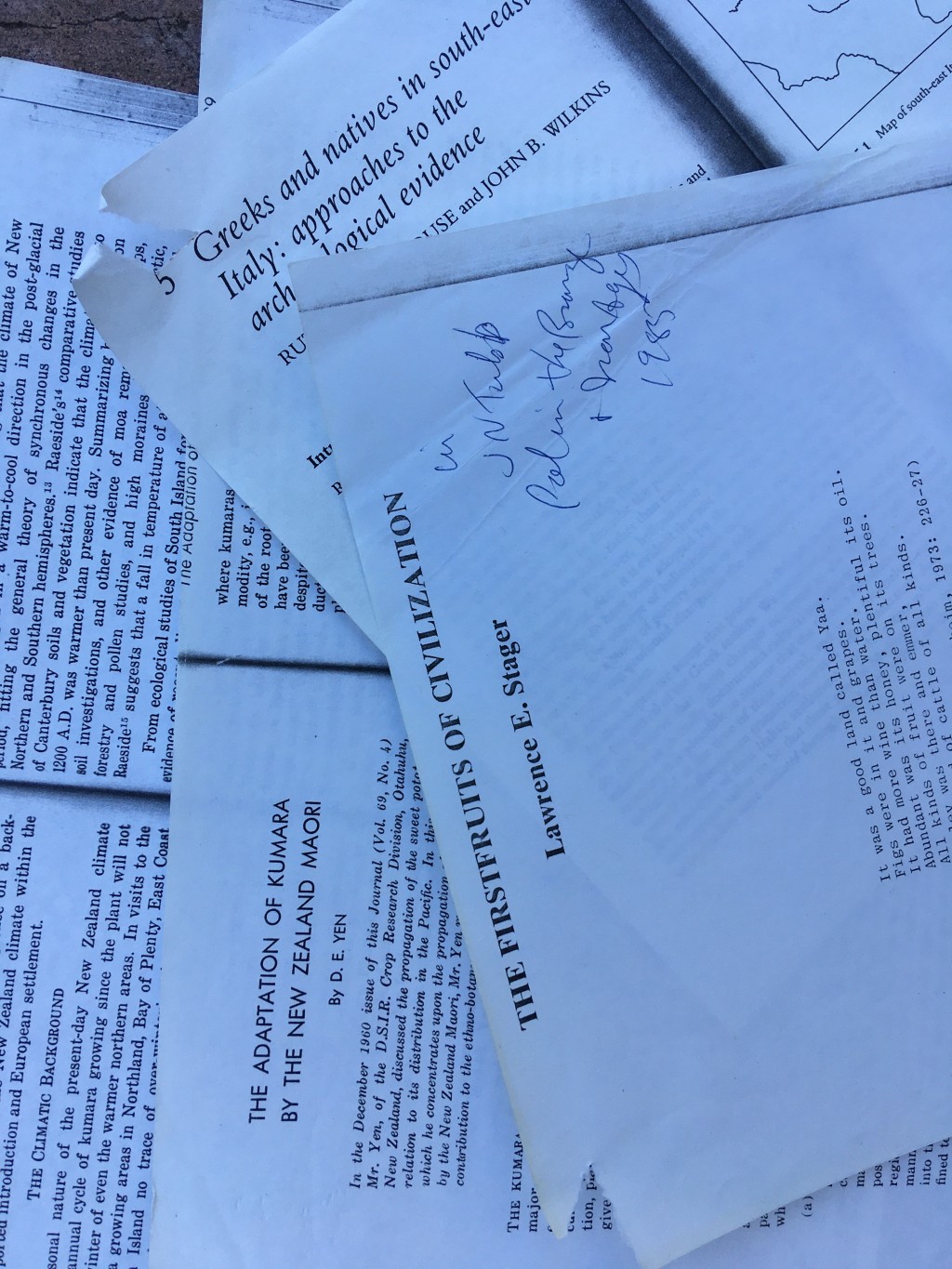

Photocopies. Photocopies of articles, of chapters in books, of research papers sent to me, of articles from National Geographic, Antiquity, and the Palestinian Expedition Fund Quarterly Statement. Drafts of papers I’ve written and stacks of offprints of the final printed version.

For any scholar who grew up in the pre anything-you-ever-want-can-be-found-online era, you’ll know what I’m talking about. I spent much of my time and most of my money as a graduate student hunting down obscure articles from PEFQS 1899 because some other article, from 1902, had mentioned it. That required standing in front of a copy machine, at a library, home, or Kinkos, and dutifully running off a copy to read, annotate, and stash into a filing cabinet.

I was one of Kinko’s first customers. Paul Orfalea started the company in 1970 in a wooden shed on Pardall Street in Isla Vista, next to UCSB where I was an undergraduate. I biked past it every day and stopped regularly to get things photocopied. I’ve been told that when I left IV, then Ann Arbor, Westwood, or Berkeley for my next academic stop, the economy came crashing down as the copy shops tried to recover from the photocopy recession. All those hours, all those pages, all those dollars coming from washing dishes at the dining hall, all went into building that library full of copies. Xerox and HP became global empires on my paltry grad student earnings.

But here we are in the internet age, when almost all of these papers, even the ones from 1899, can be found by clicking a f

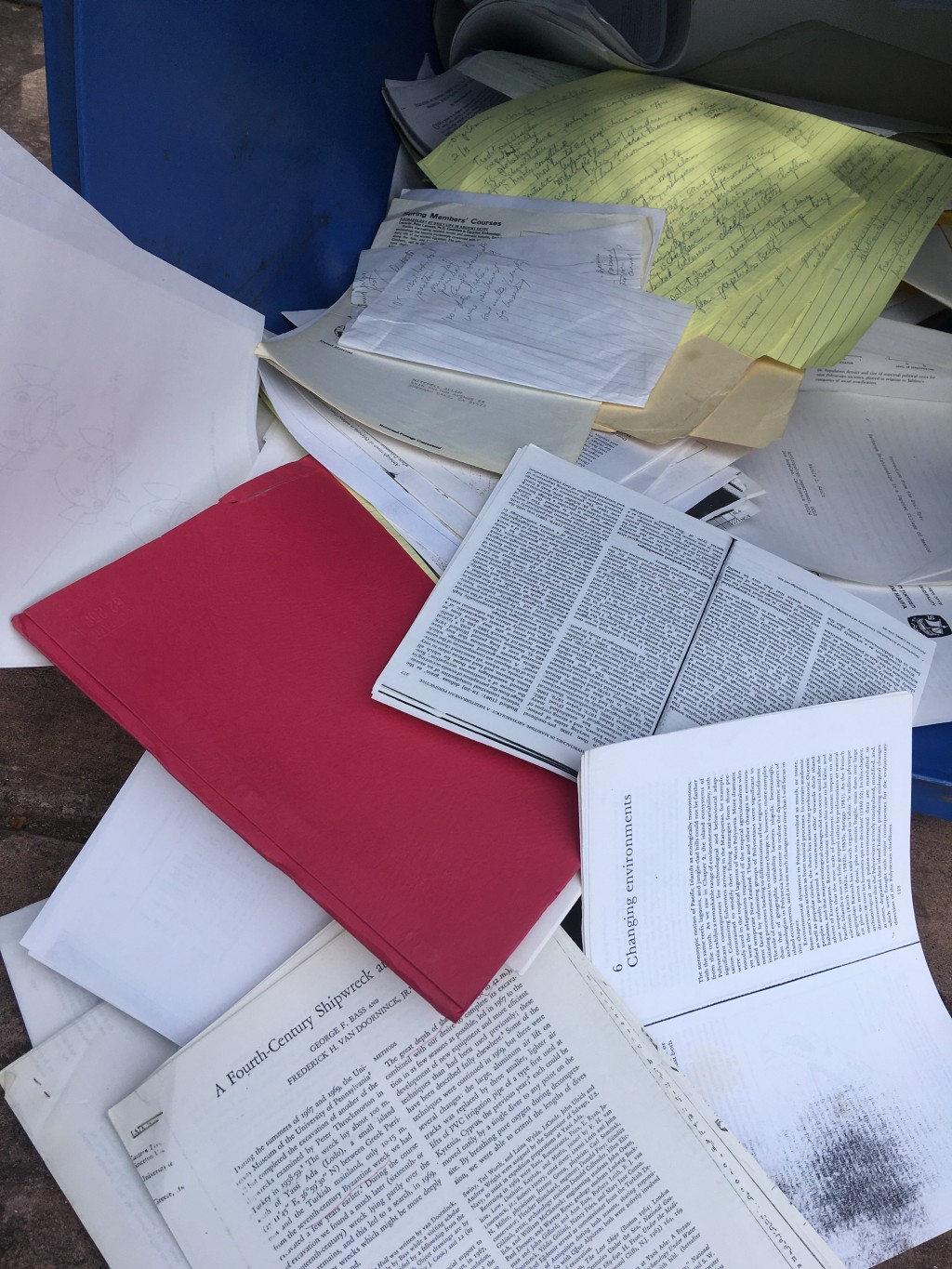

One cabinet down. And I am bereft.

Out went all those preliminary excavation reports of Tell Hesi, Ashdod, Achziv. Quantitative studies of Iron Age fauna of the Negev. Ceramic typologies of the Late Bronze Age. Philistine origins. Roman demises. Gone. The papers I collected for my presentation to Tim Earle’s Polynesian archaeology seminar. Polynesia? When are you ever gonna use this? Gone. Whole books of Assyrian palace texts that had been carefully (and illegally) reproduced. Gone. The transcription of Hamurrabi’s code from the original stele with which I tried to learn Akkadian. Gone. Our recycle bin runneth over.

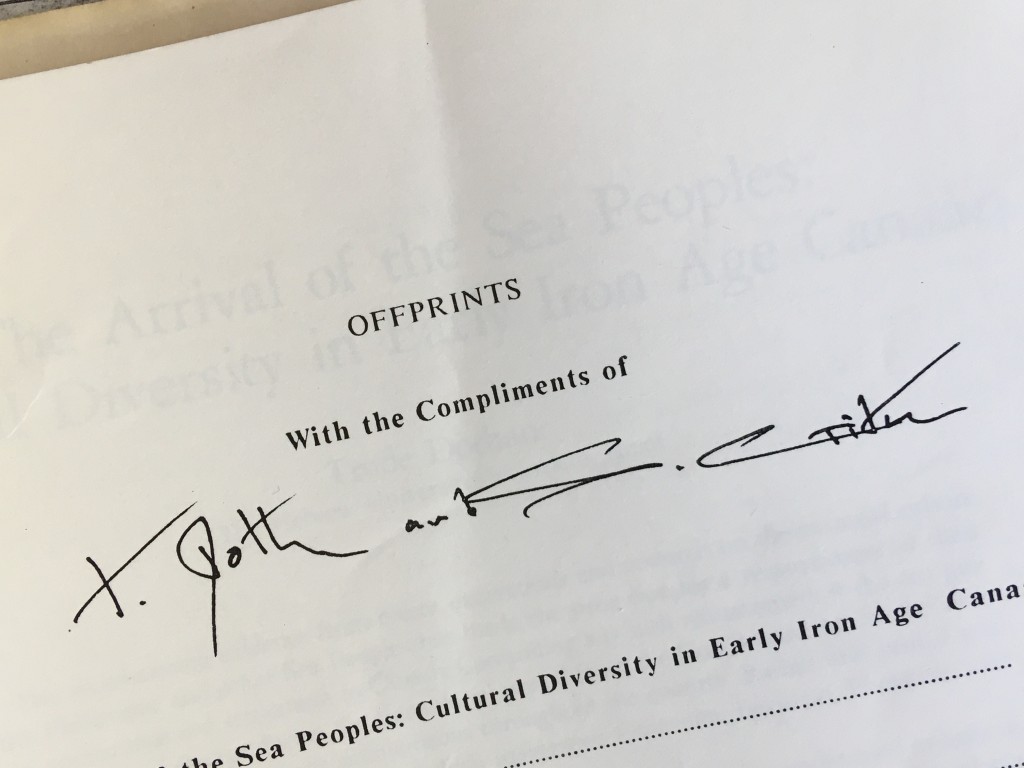

But I didn’t discard everything. Some papers sent to me by friends with requests for comments that have been scribbled all over. A folder of one or two folks whose work I always like. A few unpublished articles from people who were or became very famous, sent to me because I was publishing them. I did toss all of sociologist Andre Gunder Frank’s manuscripts that I had stashed. He may have been famous, but he was also an asshole. Articles on a few topics that I may, just may, go back and think about a bit more some day since I’m masquerading as a scholar now.

In my first seminar presentation in grad school in Ann Arbor, I tackled Palestinian bichrome ware. Dating to about 3500 years ago, it had been found at one of the earliest digs in the Levant and given that descriptive name. But it was always an anomaly, looking much more like the pottery from Cyprus at the time than from Israel. So I made a case for it being misnamed. Using one part research and two parts bluster, I proposed it that should have properly been called Cypriote bichrome ware and its origin was miscast. No easy feat to give your first grad paper by challenging

I kept that photocopy.

I carefully skirted the drawer holding all my writings, notes, maps, and photos from my dissertation work, cheerfully named Co

“I have a suspicion I performed my most valuable function in reading your draft by just agreeing to, which prompted you to actually produce one.” He was right. He also said my first draft was “overwritten.” He was right again.

I’ll keep that letter too.

There will come a day when I will look for one of those articles and discover that not only is it not online but it now has been shredded, reconstituted, and come back to life as part of an Amazon Prime box. I will shed a tear or two that day. My kids won’t understand that at all. If you’re my age and a scholar, maybe you will.

(c) Scholarly Roadside Service

Back to Scholarly Roadkill Blog

Scholarly Roadside Service

ABOUT

Who We Are

What We Do

SERVICES

Help Getting Your Book Published

Help Getting Published in Journals

Help with Your Academic Writing

Help Scholarly Organizations Who Publish

Help Your Professional Development Through Workshops

Help Academic Organizations with Program Development

CLIENTS

List of Clients

What They Say About Us

RESOURCES

Online Help

Important Links

Fun Stuff About Academic Life